Though we have seen a quantity of completely different robotic water striders over time, scientists are nonetheless discovering intelligent new points of the bugs to duplicate. Lately, as an example, researchers created a strider-bot that zips throughout the water’s floor through followers on its ft.

Measuring solely 3 mm lengthy, water striders of the genus Rhagovelia actually are one thing particular.

On the ends of their two lengthy center legs – that are those they use for propulsion – there are feathery appendages which fan out upon hitting the water’s floor. Because the legs are then drawn again on the ahead stroke, these now-underwater followers cup the water just like the webs between a frog’s toes, quickly rowing the insect ahead.

Upon being drawn up out of the water on the finish of the stroke, the moist strands of the fan wick collectively into some extent – form of just like the bristles of a freshly dipped paintbrush. This makes the appendage extra streamlined because the leg swings again ahead, on its strategy to execute one other stroke.

Victor Ortega-Jimenez/UC Berkeley

The followers enable the bugs to shoot throughout the floor at speeds of roughly 120 physique lengths per second. What’s extra, by deploying a single water-grabbing fan on only one aspect, the striders can pull off 90-degree turns in about 50 milliseconds.

Evidently, in the event you had been designing aquatic robots, it might be nice if they had been so agile. With that thought in thoughts, scientists from the College of California-Berkeley, Korea’s Ajou College, and the Georgia Institute of Expertise determined to take a more in-depth take a look at Rhagovelia.

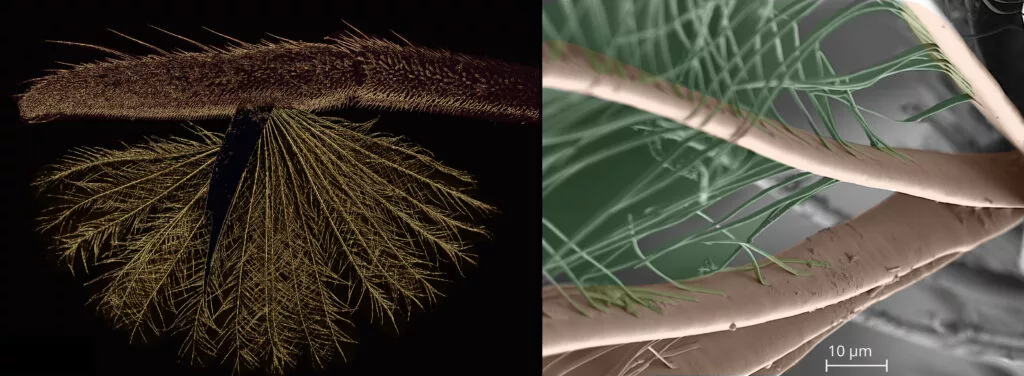

Using electron microscopy, Ajou’s Prof. Je-Sung Koh and postdoctoral researcher Dongjin Kim discovered that the person strands of every fan include a central flat, versatile, ribbon-like strip with smaller barbules branching off the edges of it – it truly is loads like a feather. This design permits the appendages to fan out underwater, to allow them to be used like an oar.

Emma Perry/Univ. of Maine and Victor Ortega-Jimenez/UC Berkeley

The scientists moreover found that the water’s floor stress offers all of the elastic pressure that’s wanted to trigger the strands to fan out. It had beforehand been assumed that the fanning motion was muscle-powered. A small quantity of muscle energy is utilized to carry the followers tense in the course of the stroke, however none is used to deploy them.

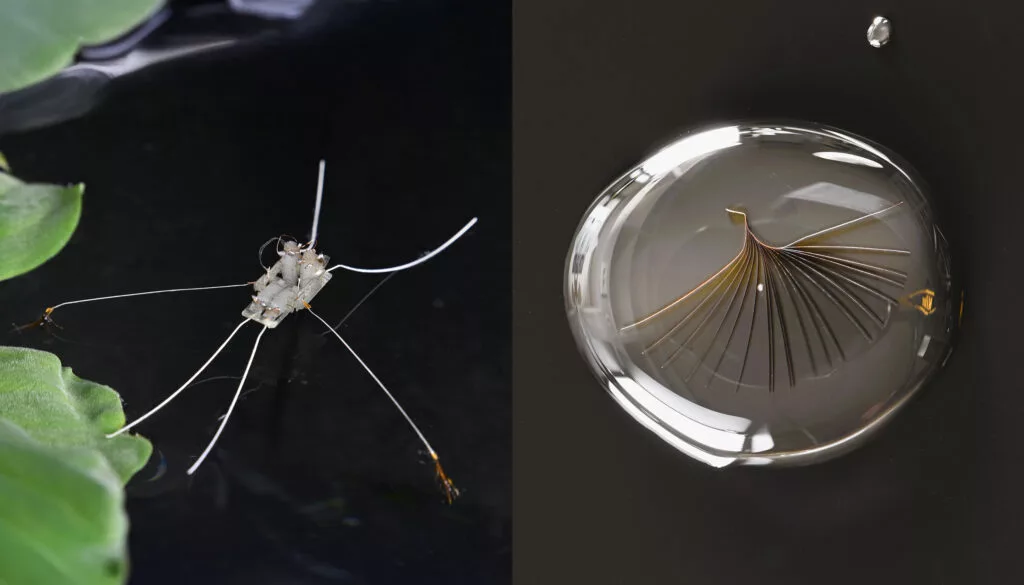

Based mostly on these findings, the group created a robotic model of the insect, named Rhagobot.

It is actually greater than its namesake, coming in at 8 cm lengthy by 10 cm vast by 1.5 cm excessive (3.1 by 3.9 by 0.6 in). On the finish of every of its two center legs is a 1-milligram Rhagovelia-like fan – full with the flat-ribbon microarchitecture – measuring 10 by 5 mm.

Ajou College, South Korea

The entire bot, which is hardwired to an exterior energy supply, weighs simply one-fifth of a gram. It is at present able to scooting throughout the water’s floor at two physique lengths per second, and making 90-degree turns in lower than half a second. It’s hoped that descendants of Rhagobot will probably be even quicker and extra agile, making them helpful in purposes comparable to search-and-rescue or environmental monitoring.

“Our robotic followers self-morph utilizing nothing however water floor forces and versatile geometry, identical to their organic counterparts,” says Prof. Koh, senior co-author of the research together with Georgia Tech’s Prof. Saad Bhamla. “It’s a type of mechanical embedded intelligence refined by nature by way of thousands and thousands of years of evolution. In small-scale robotics, these sorts of environment friendly and distinctive mechanisms can be a key enabling expertise for overcoming limits in miniaturization of typical robots.”

A paper on the analysis, which was led by UC Berkeley’s Asst. Prof. Ortega-Jiménez, was lately printed within the journal Science. You’ll be able to see Rhagobot in motion, within the video beneath.

Water Bugs, and a New Robotic, Use Fan-like Propellers

Sources: UC Berkeley, Georgia Tech