The rapid expansion of new top-level domains (TLDs) has amplified a long-standing security vulnerability: numerous organizations, having set up their internal Microsoft authentication mechanisms several years ago, employed domains tied to TLDs that did not yet exist at the time. Without warning, some users are carelessly sharing their Windows login credentials with publicly accessible domain names, essentially broadcasting their sensitive information to anyone who might be listening. One safety researcher has taken on the daunting task of mapping the scope of this pervasive threat, striving to contain its far-reaching impact.

The issue at hand is a well-known safety and privacy threat referred to as “intra-net fragmentation”, where domains intended solely for use within an internal company network end up conflicting with domains that can typically be resolved on the public Internet.

On a personal corporate network, home Windows computer systems troubleshoot various issues using Microsoft’s innovation, collectively known as Azure Active Directory (Azure AD), which is an umbrella term encompassing a wide range of identity-related services in Windows environments. One crucial aspect of how devices find each other is through Windows’ “NetBIOS” functionality, a form of network shorthand that facilitates the discovery of other computers or servers without requiring a fully qualified domain name (FQDN) for those resources.

Within the internal network instance, workers can access the shared drive “drive1” by simply entering “drive1”, without needing to specify the full domain name “drive1.internalnetwork.instance.com”. Windows automatically resolves the rest.

Despite the benefits, problems can arise when a corporation builds its Energy Listing community atop a platform it neither owns nor controls. While some may view this approach as unorthodox for designing an organization’s authentication system, it is worth noting that numerous companies established their networks before the proliferation of many new top-level domains such as .community, .inc, and .llc.

In 2005, an organization opted to deploy Microsoft’s Active Directory service across the globe, likely reasoning that since .llc was not yet a routable TLD, the domain would simply fail to resolve if the group’s Windows computers were ever accessed remotely outside of their native network.

In 2018, the LLC TLD emerged, officially launching its domain promotion efforts. Once a firm.llc was registered, anyone with such an entity could intercept and manipulate its Microsoft Windows login credentials without being detected, effectively allowing for redirections to malicious destinations.

John, a pioneering figure in the field of safety consultancy, is just one of several researchers endeavoring to map the scope of the namespace collision problem. With extensive expertise in penetration testing, Caturegli has masterfully leveraged these collisions to execute targeted attacks on organizations that have commissioned him to scrutinize and test their cybersecurity fortifications. Over the past year, Caturegli has consistently mapped this vulnerability across the web by tracing subtle clues hidden within self-signed security certificates, for instance: SSL/TLS certs).

Researchers have been actively monitoring the open web for self-signed certificates referencing domains across various top-level domains (TLDs) that are vulnerable to exploitation by companies, including .io, .dev, and others.

The Seralys team uncovered over 9,000 unique domain references across various top-level domains (TLDs). The evaluation revealed significant disparities in uncovered domains among top-level domains (TLDs), with approximately 20% of those terminating in .advert, .cloud, or .group remaining unused.

“The complexity of the challenge far exceeds my initial expectations,” Caturegli admitted during a conversation with KrebsOnSecurity. As part of my comprehensive analysis, I have also identified key authorities, international organizations, and critical infrastructure that require consideration. which have such misconfigured property.”

REAL-TIME CRIME

Among previously listed top-level domains (TLDs), several are not new and actually correspond to country-code TLDs, such as .it for Italy, and .to for the small island nation of Tonga. Caturegli warned that many organizations were under the misconception that a URL ending in .advert represented a convenient shortcut for an internal directory setup, oblivious to the fact that someone could actually register such a domain and capture all Windows credentials and unencrypted traffic.

Although Caturegli discovered an encryption certificate in active use, the registration process remained available and unclaimed for the area. Prior to registration, potential clients are mandated to specify a distinct and memorable trademark for their website in the .advert registry.

Despite being undaunted, Caturegli found a site registrar willing to promote the area to him for $160 and handle the trademark registration for an additional $500; subsequently, he set up a company in Andorra that processed trademark applications at half the cost.

Following the setup of a DNS server for memrtcc.advert, Caturegli suddenly received a barrage of authentication requests from numerous Microsoft Windows-based computers. A database query revealed that each request contained a username and a hashed Windows password, leading Caturegli to research the usernames online; she discovered that they all pertained to law enforcement officials based in Memphis, Tennessee.

“It seems that all the police cars there have laptops installed in them; they’re all connected to a memory stick area that I now own,” Caturegli said wryly, pointing out that “memrtcc” actually stands for “memory”.

Caturegli’s decision to compile an email server report was unexpectedly triggered by a spam campaign for MemRTCC, leading to his receipt of automated messages from the police division’s IT support team and numerous trouble tickets regarding the city’s Okta authentication system.

The information safety supervisor for the City of Memphis confirmed that the Memphis Police Department has been sharing its Microsoft Windows login credentials with the city, and that officials were collaborating with Caturegli to transfer the account to a more secure platform.

“We are collaborating with the Memphis Police Department to significantly alleviate the issue in the interim,” Barlow said.

Area directors have long been incentivized to utilize internal domains due to this TLD being non-routable on the open internet. Despite this, Caturegli noted that numerous organisations seem to have misunderstood the concept, with some prioritising their internal Energetic Listings infrastructure across the entire, fully routable network.

Caturegli acknowledged his awareness of this issue due to defensively registering native.advert, currently used by several major organizations for active directory setups – including a European mobile network provider and a prominent company in the UK.

A single wireless control plane to unify them all?

Caturegli has defensively registered numerous domains ending in “.advert”, including inner.advert and schema.advert. Despite being a secure area, there may possibly be the most dangerous sector within. WPAD stands for Web Proxy Auto-Discovery, which is a historical, on-by-default function embedded in each model of Microsoft Windows designed to simplify the process of automatically discovering and obtaining proxy settings required by the local network.

When groups choose an advert area without personalising their energetic listing set up, they may encounter a multitude of Microsoft techniques repeatedly trying to reach wpad.advert on machines with proxy automated detection enabled?

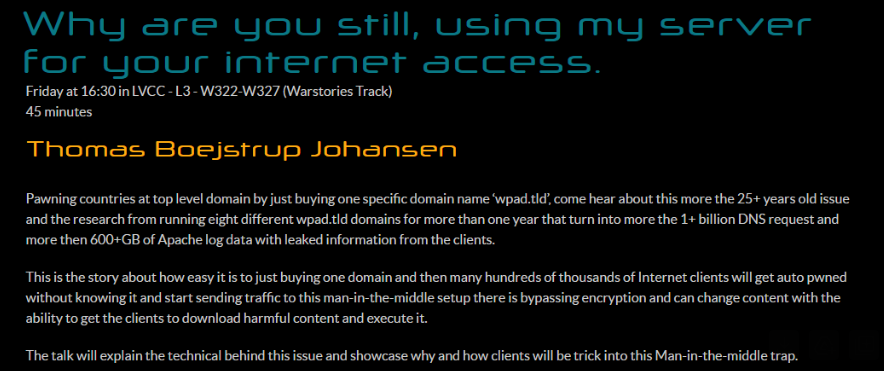

For over two decades, security experts have consistently sounded the alarm about the vulnerabilities of WPAD, cautioning that its design makes it susceptible to exploitation by malicious actors. At last year’s DEF CON safety conference in Las Vegas, for instance, a researcher observed a peculiar phenomenon after registering their session: Instantly, a torrent of WPAD requests flooded in from Microsoft Windows systems in Denmark, where namespace collisions had compromised their Active Directory environments.

Picture: Defcon.org.

Catering to his part, Caturegli set up a server on wpad.advert to detect and report the web addresses of any Windows systems attempting to access servers. He observed that within a week, his setup received more than 140,000 hits from hosts worldwide trying to connect.

The primary drawback of WPAD lies in its origins as an innovation intended for static, trusted workplaces, rather than today’s dynamic mobile-first environments and distributed workforces.

The primary obstacle to resolving namespace collision issues is the perceived high cost of rebuilding an organization’s energetic listing infrastructure around a new domain name, which many consider too risky, considering the relatively low potential threat.

Citing Caturegli’s assertion, it appears that ransomware groups and other cybercriminal entities can potentially siphon large quantities of Microsoft Windows login credentials from numerous companies for a relatively modest initial investment?

“With this straightforward technique, you can gain a preliminary foothold without the need for a precise attack,” he said. You’re anticipating that a misconfigured workstation will seamlessly connect with you and transmit its credentials without issue.

As cybersecurity experts warn of the increasing threat of namespace collisions being exploited by malicious actors to launch devastating ransomware attacks, the onus is on organizations to take proactive measures to safeguard their digital assets. In 2013, a pioneering area title investor, who had registered a diverse array of alternative domains such as bar.com, place.com and tv.com, sounded the alarm repeatedly about the impending introduction of over 1,000 new top-level domains (TLDs), warning that this move would lead to an exponential surge in namespace collisions. So deeply concerned with the matter was O’Connor that he actively sought input from researchers, potentially identifying a premier approach to alleviating the problem.

Mr. O’Connor’s most notable claim to fame stems from a unique circumstance where, over an extended period, thousands of Microsoft PCs repeatedly bombarded his domain with authentication credentials from organizations that had misconfigured their Active Directory settings to use the “corp.com” suffix in their naming convention.

Microsoft’s use of corp.com served as an illustration of how to set up Active Directory in certain versions of Windows NT. A significant portion of website visitors accessing corp.com originated from Microsoft’s internal networks, suggesting that a portion of Microsoft’s internal infrastructure was inadvertently exposed. When O’Connor claimed he could auction off corp.com to the highest bidder in 2020, Microsoft allegedly emerged as the successful buyer.

“I believe the biggest downside is like a city that intentionally built its water supply using lead pipes,” O’Connor told KrebsOnSecurity, “or companies that knowingly provided these services without informing their customers.” “This isn’t a surprise factor akin to Y2K, where everyone was caught off guard by what happened.” Individuals knew and didn’t care.”